Happy 2026! It should be the seventh year of our Roaring 2020s scenario, with three more to go. We first wrote about this scenario on August 11, 2020, in our Morning Briefing titled "Another Roaring Twenties May Still Be Ahead." We predicted, "So far, the 2020s has started with the pandemic, but there are plenty of years left for the prosperous 1920s to become a precedent for the current decade. If so, the driver of the coming boom will be technology-enhanced productivity, as it was during the 1920s."

So far, so good. Productivity grew at a fast clip last year and should do so again in 2026. If it does, real GDP could increase 3.5% this year, and inflation should fall to 2.0%. On the demand side of GDP, consumer spending should remain resilient as retiring Baby Boomers continue to spend their $80 trillion in net worth. If that’s the case, then disposable personal income growth is likely to be slow, and the savings rate is likely to fall toward zero and even turn negative by the end of the decade. Capital spending should remain strong, especially for technology hardware and software. Both fiscal and monetary policies will be even more stimulative in 2026 than last year.

In our economic outlook, S&P 500 earnings per share should increase 15% to $310 this year and then 13% to $350 in 2027. Assuming so, then the S&P 500 should rise to 7,700 by the end of this year. The 10-year Treasury bond yield should average 4.50% this year within a range of 4.25% to 4.75%. There's no need for additional Fed rate cuts in this scenario.

We are still assigning subjective probabilities of 60% to our Roaring 2020s scenario, 20% to a meltup/meltdown scenario, and 20% to a 2026 recession. If the Fed continues to cut the federal funds rate, we will raise the odds of a meltup/meltdown. The most significant recession risk is that an excessively stimulative combination of monetary and fiscal policies drives up consumer prices, commodity prices, and asset valuations. Such widespread inflationary pressures would likely incite the Bond Vigilantes. Another risk is that productivity growth proves lackluster, which weakens real wage growth; that, along with the "no net hiring" economy, depresses consumer spending and the overall economy.

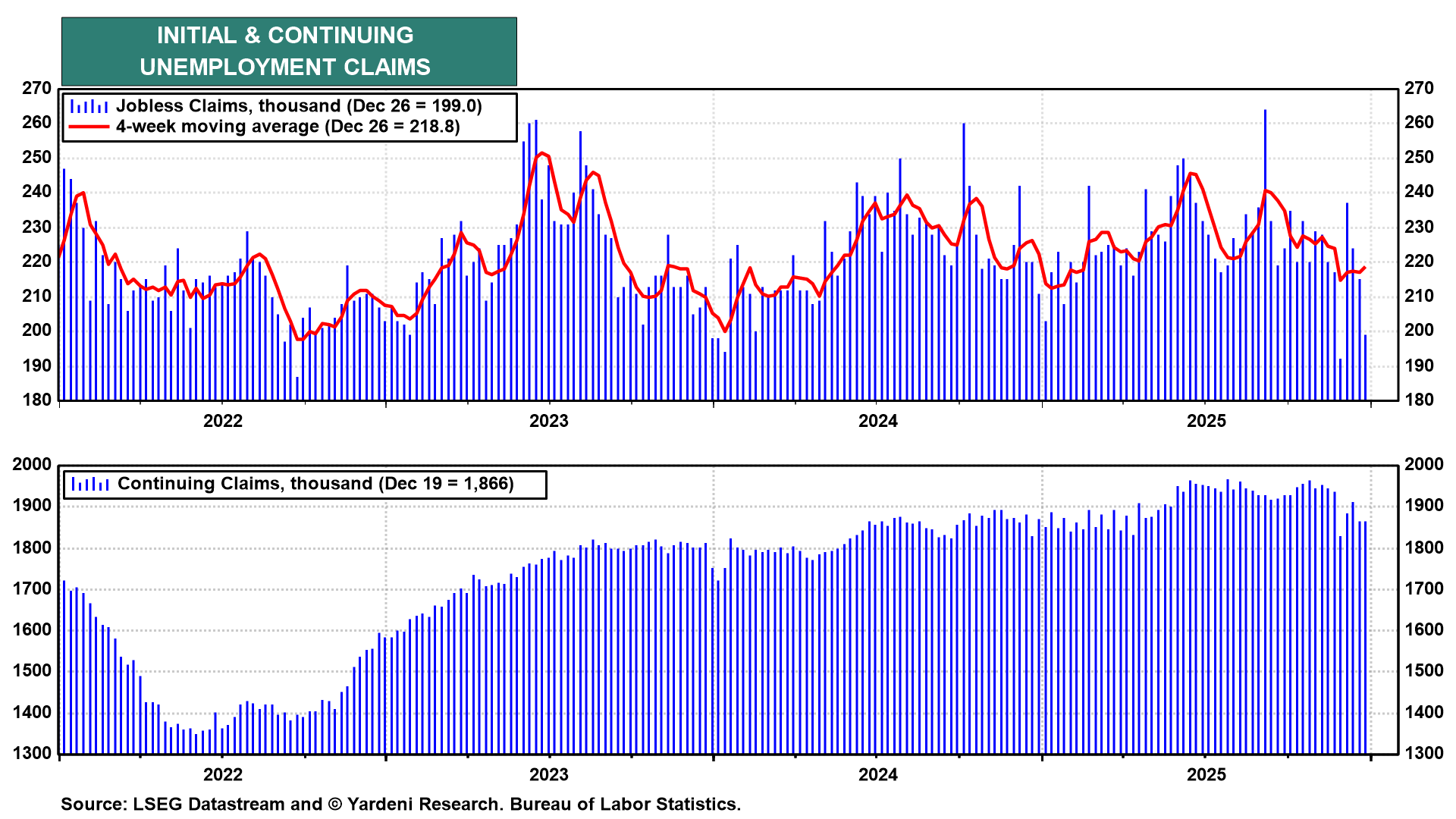

The biggest surprise this year might be a rebound in payroll employment growth. That's supported by the decline in initial unemployment claims at the end of 2025 (chart). The coincident drop in continuing unemployment claims suggests that the duration of unemployment is decreasing.

We disagree with the widespread view that the economy is challenged by a "no-hire, no-fire" labor market. In fact, the pace of hiring in October was relatively normal, at 5.1 million workers (chart). However, that pace equaled separations attributable to quits and layoffs. In the past, hiring typically exceeded separations when the economy was growing, as it is now. It's a "no-net-hiring" labor market.